Assessments, Challenges, and the Best Possible Practice

In our last article, we broke down the design principles of effective interdisciplinary programs. But there’s one thing even good design can’t sidestep: how to measure what really matters.

The Problem with Measuring Complex Learning

In most education and corporate training, assessment is straightforward: test the knowledge, grade the answer, log the result. But interdisciplinary capability doesn’t fit into multiple-choice questions. It’s not just “knowing” — it’s transferring methods from one field to another, adapting under constraints, and producing something that works in the real world.

That’s hard to measure — and even harder to measure at scale. Which is why, in many programs, assessment is an afterthought or reduced to vague participation scores. The result is predictable: graduates who enjoyed the experience but can’t demonstrate to an employer, a regulator, or themselves that they can actually do the thing.

Why Interdisciplinary Assessment Is Different

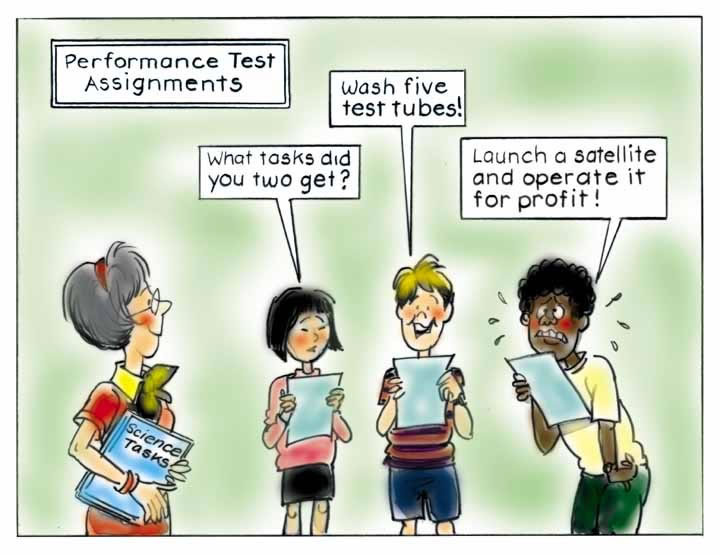

Traditional assessment looks for correct answers within one discipline’s rules. Interdisciplinary work lives in the grey space between disciplines, where “correct” depends on how well the learner integrates ideas and adapts them to context.

Global examples show this is solvable, but not simple. The NSF’s IGERT program assessed doctoral students through multi-dimensional rubrics — combining peer feedback, mentor evaluation, and performance on authentic research deliverables. The International Baccalaureate’s extended essay and Theory of Knowledge use reflective components and real-world scenarios to assess transfer, not just recall.

The common denominator? Performance-based, authentic assessment that mirrors the messy conditions of the real world.

The Ideal vs. the Best Possible Case

In an ideal world, every interdisciplinary program would:

- Run multi-month, team-based projects with live stakeholders.

- Include multiple assessors from different disciplines.

- Track learner performance for months after the program ends.

But most schools, universities, and companies face constraints:

- Time — a semester, or even a corporate training cycle, may be too short for fully embedded projects.

- Budget — bringing in external experts and assessors is expensive.

- Data access — in industry settings, real datasets may be proprietary or sensitive.

- Scalability — assessment methods that work for a cohort of 20 may collapse under 200.

That’s where the “best possible” case matters more than the ideal.

What Best Possible Practice Looks Like

EducAI8’s approach to assessment in real-world conditions focuses on balancing rigor with feasibility:

- Capstone artefacts — a prototype, policy brief, or business plan, assessed against a rubric co-designed with industry.

- Principle extraction tasks — short reflective pieces where learners explain how their project insights could transfer to a different domain.

- Multi-source evaluation — input from facilitators, industry mentors, and peers to capture different perspectives.

- Post-program signal — a lightweight follow-up survey or short re-application task 3–6 months later, to check retention without heavy resourcing.

For example, in a Sustainability and Business Strategy program, a learner team might present a circular-economy product model to a panel including an environmental scientist, a supply-chain manager, and an investor. The panel’s rubric scores are combined with a short reflection from the team on how the same approach could be adapted to a different sector — a double-check for transfer capability.

The Hard Truth

Assessing interdisciplinary capability is not a perfect science. The best programs accept trade-offs: you can’t measure everything, but you can measure the right things well enough to give employers, institutions, and learners confidence in the outcome.

And that’s the point — the goal is not to build a pristine lab model, but to design an assessment system that works under real-world constraints, keeps fidelity to the learning goals, and produces evidence of capability that matters beyond the classroom.

Closing

That’s the balance every institution and employer need to strike. At a minimum, the must-do is clear: shift from generic training to domain-specific, deliberately designed learning with assessments that capture real transfer. The good-to-do is building in richer, mixed-method evaluation — pairing performance evidence with longitudinal follow-up to see if skills stick and scale. The ideal is a fully embedded, sector-wide approach where program design, delivery, and assessment are co-created by practitioners, researchers, and educators, and refined over time. That last tier is rare, but attemptable — and it’s exactly the kind of real-world, high-rigor work EducAI8 exists to make happen with partners ready to push the boundaries.

Leave a Reply